To mark the centenary of the foundation of the Trento Natural History Museum in 1922, we have collected 10 fragments from the history of the museum in an exhibition that explains the meaning of what we do. Our search through the archives for documents, photographs, instruments, and artefacts from the past provided a chance to bring to light the stories of the protagonists, human and non, who have made the MUSE a symbolic place for the encounter of scientific knowledge and the public. A story of rigour and passion, science and politics, memory and visions of the future.

The museum’s historical collections are the main players of the MUSE 100 exhibition, and the instruments, minerals, plants, and animals that have re-emerged from the archives testify to visions of the world and social systems. The MUSE collections are, in fact, as much about biodiversity and mountain territories as the people and system of values that organised them, and so through these objects we relive stories of men, women and shared cultural dynamics.

In emphasising how conservation, research and promotion have always been the cornerstones of what we do, the exhibition underlines the historical and current importance of the museum not only for the study of the territory and its ecosystems, but also for its ability to provide tools useful for the protection, management and valorisation of biodiversity in the Autonomous Province of Trento–that conservation of nature as a “social necessity” so often reiterated by Gino Tomasi, the museum’s director from 1965 to 1992.

The MUSE 100 exhibition allows us not only to retrace the museum’s early foundations, but also to collectively imagine the future of an entire institution that, in a century of history, has become a symbolic place for the encounter between science, nature and society.

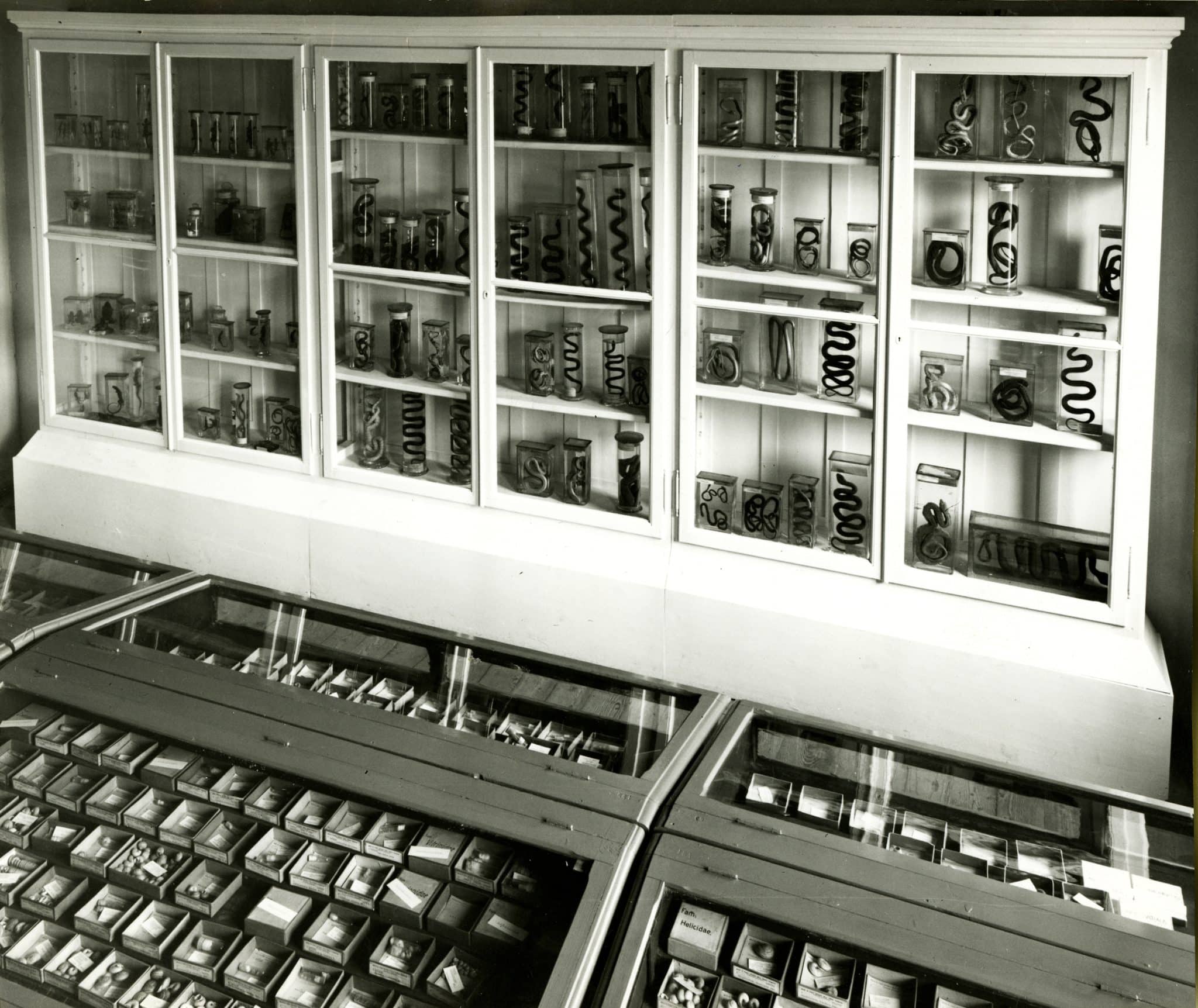

Photo 1: Display case with systematic museum layout in the via Verdi building, circa 1960 – 1970 – © MUSE Archive

Photo 2: Museum’s microscopy laboratory, 1922 – photo G.B. Unterweger

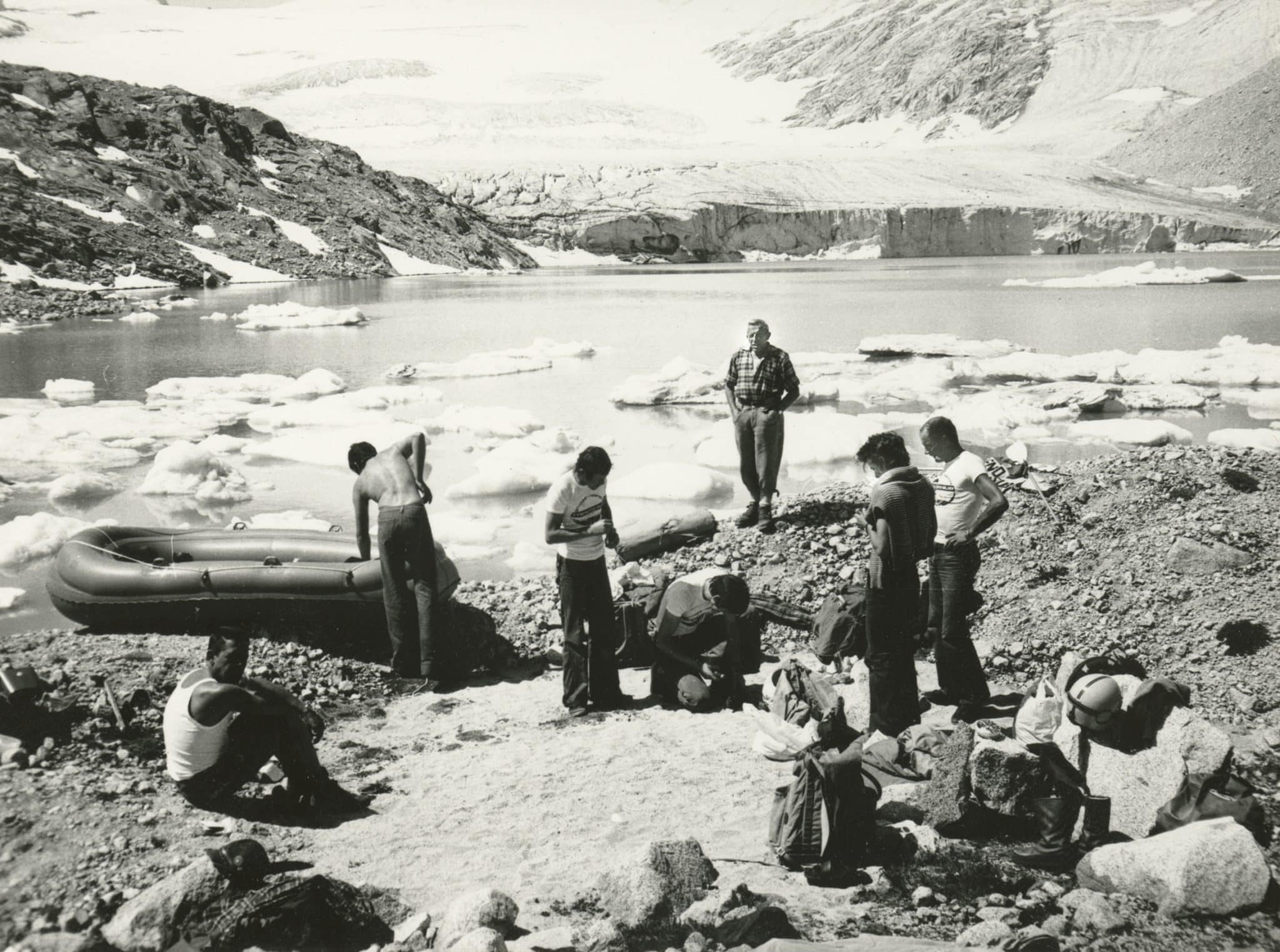

Photo 3: Expedition to Lake Lares in Val di Genova, 1976 – photo Mario Cont

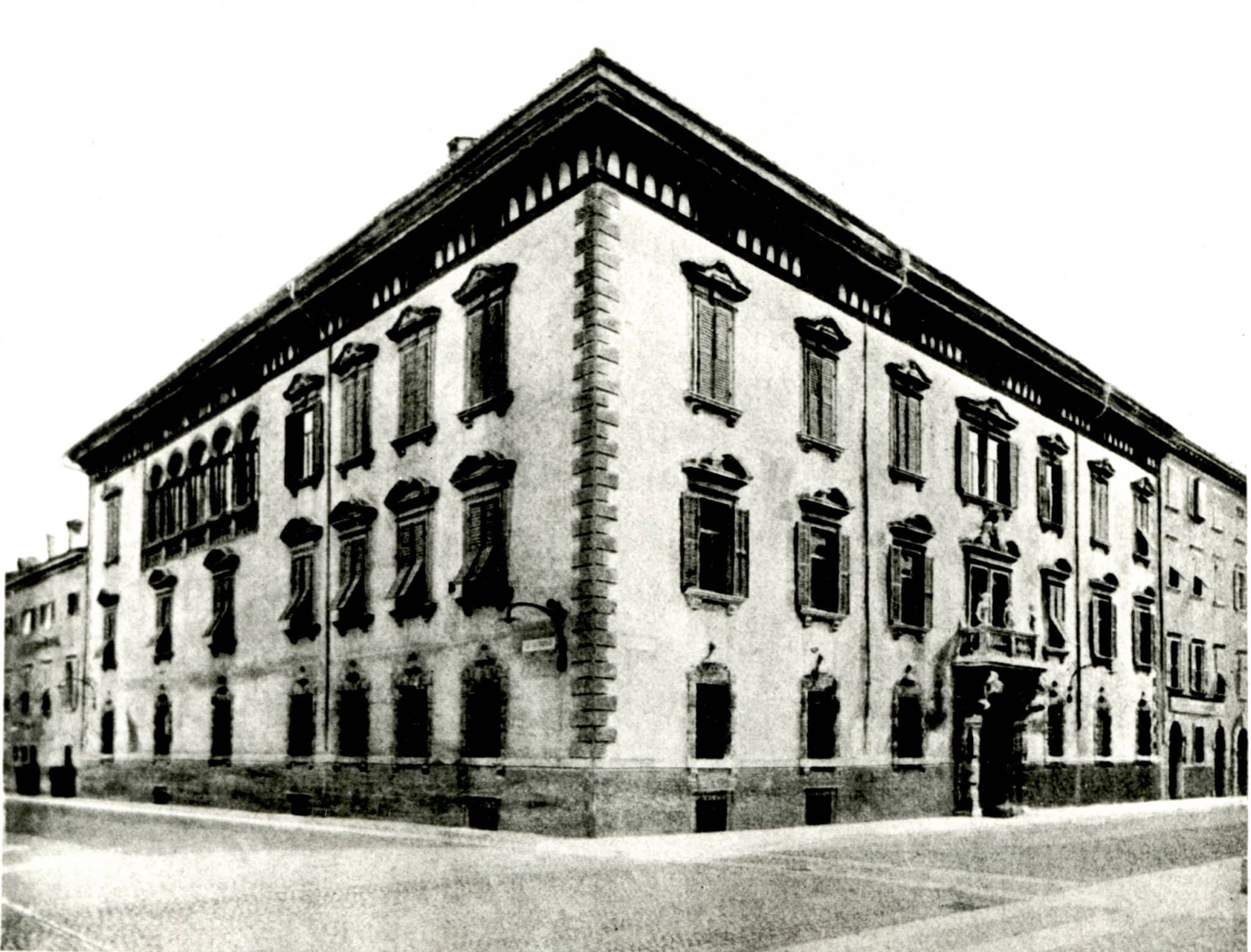

Photo 4: Palazzo Sardagna in via Calepina – © MUSE Archive

Photo 5: Transfer from via Calepina, 2013 – © MUSE Archive

Stages of the exhibition

MUSE is part of a centuries-long history marked by the foundation in 1922 of the Trento Natural History Museum. In this exhibition we have put together fragments of a long evolutionary path to explain the deep-rooted reasons behind what we do. An opportunity to get to know the protagonists, human and non, ideas, practices, and events that have made MUSE a symbolic place of encounter for scientific knowledge and the public. A story of rigour and passion, science and politics, memory and visions of the future.

The material memory of the world

In museums we preserve the material memory of the world on which we base narratives of the present and visions of the future. We save objects from oblivion, entrusting museums with the task of preserving them in time and giving them value by indulging the innate human urge to tell stories from objects. Museum collections are therefore witnesses to a certain worldview and social system: they tell us as much about biodiversity and mountain environments as they do about people and the value system that organised them. They are objects that speak of a plural us.

Changing yet staying true to ourselves

Constantly changing but always recognisable, innovative but firmly rooted in the pillars of our work: conservation, research, enhancement. We transform by acquiring new exhibits, moving to new locations, but also driven by the changing gaze of the people who make the museum. We innovate by following cultural changes and the new questions posed by societies. We evolve because we are portions of the world and as such in constant transformation. New looks, new languages, new methods, audiences, questions and a solid benchmark: our collections.

Research, imagine, involve

“The function of a nature museum is first to increase and then to disseminate scientific knowledge,” maintained James Smithson, father of the Smithsonian Institution, the largest museum complex in the world. Since its foundation, our museum has been a place of research: we research driven by an innate curiosity for nature, we analyse the territory and ecosystems to provide useful tools for their management, we work to enhance the natural and cultural heritage that surrounds us. We proudly occupy the borderline between production of knowledge and participated dialogue with society founding our actions on the scientific method.

Stories that dig deep

Geology, palaeontology and prehistory are foundational disciplines for our museum. The oldest collections of which we have evidence, dating back to the late eighteenth century, consist of minerals, rocks, and fossils. After its foundation in 1922, for two decades the museum was headed by the geologist Giovanni Battista Trener. After the Second World War, the museum’s progressive interest in archaeology took the form of some of the most important excavation campaigns in the Alps, identifying the museum as a place for the preservation and valorisation of the materials discovered. Study of the landscape is still today our key to construction of the present.

An idea of nature

Specialised expertise in the field of nature has enabled the museum to make a decisive contribution to the knowledge of biodiversity and environments in the Autonomous Province of Trento. Our policy making stems from the idea of nature conservation as a social necessity. It is a role that we still claim today, convinced that museums, located at the intersection between the public and the government of public affairs, can make a decisive contribution to the cultural and political redefinition of relations with those different to us on the basis of a fundamental imperative: we are nature.

Education, pleasure, sharing

“Museums should constantly ask themselves,” warned museologist Gail Anderson, “whether their founding values resonate with those of society. Museums are in fact simultaneously an expression of society and at its service. The programmes for the public developed by the museum, based on scientific rigour, are guided by the cardinal criteria of accessibility and inclusiveness: exhibitions, educational activities, and participatory projects offer diversified experiences for education, pleasure, reflection, and the sharing of knowledge.

Who makes a museum?

The MUSE is a well-structured space for participation. We are a network of sites and affiliated centres where more than 250 people work in dialogue with people and institutions, with the scientific community, companies, the third sector and all those who recognise in the museum an opportunity to meet, dialogue, and grow. Citizen Science projects, scientific journals, and spontaneous groups that have sprung up over the years show that this is a participatory and activist museum.